When dealing with sales forecasts that concern fast-moving as well as slow-moving items, we must account for the non-proportional scaling of relative forecast uncertainty with selling rates, which largely determines the achievable level of precision.

- For the same forecast quality, predictions for slow-moving items unavoidably come with a lower absolute but higher relative error than for fast moving ones. Avoid the naïve scaling trap: If your forecast seems to struggle with slow sellers, assess to which extent the increase in relative error when moving towards low velocities is expected.

- There is no hard boundary between ‘slow’ and ‘fast’ movers. Don’t categorize items into different evaluation methodologies, but make sure your evaluation treats all predicted selling rates appropriately.

- Do you encounter many very slow-moving items in your analysis? Challenge that evaluation and make sure your aggregation time scale matches business reality — you don’t take daily business decisions on non-perishable slow-movers.

When abroad, try local, fresh and perishable food specialties

Traveling, though not easy in pandemic times, is an opportunity to learn about other cultures, landscapes and, of course, enjoy great food. Even in today’s connected and globalized world with multi-national retailers that try to instantaneously fulfill every possible wish everywhere on the planet, certain products are simply not offered at all in some places. You might not expect this piece of advice in a blog post on counting statistics, but a direct consequence of our discussion below will be: To culinarily make the most out of your travel abroad, explore the ultra-perishable, fresh specialties. Try fresh fruit in Rio de Janeiro, oven-hot pretzels in Munich and raw seafood in Busan.

Indeed, it’s hard to find traditional Bavarian pretzels in Busan, it’s impossible to buy raw sea cucumber in Rio de Janeiro (as far as we know), and travelers from South America are amused by the restricted choice of fresh fruit in northern European supermarkets. What are the common aspects of these products? They are both perishable and they would be a niche market if sold outside of their original place. Indeed, you get pickled kim chi, exported Oktoberfest beer and cachaça all over the world. But products that retailers would call both ‘ultrafresh’ (very perishable, only good for a day or so) and “slow-selling selling” (likely to not sell on a given day) is never offered, ever, anywhere.

Why is that? Why don’t Brazilian supermarkets try to satisfy the admittedly tiny but certainly existing demand for raw sea cucumber? If 100 sea cucumbers are sold each day in a shop in Busan, and the demand is one per day in Rio de Janeiro, why is the former large demand being addressed by Korean retailers, but the latter is not addressed by Brazilian stores? What is so fundamentally different between a fast-selling perishable item — say, a strawberry in Europe — and a slow-selling selling one — say, a raw sea cucumber in Brazil?

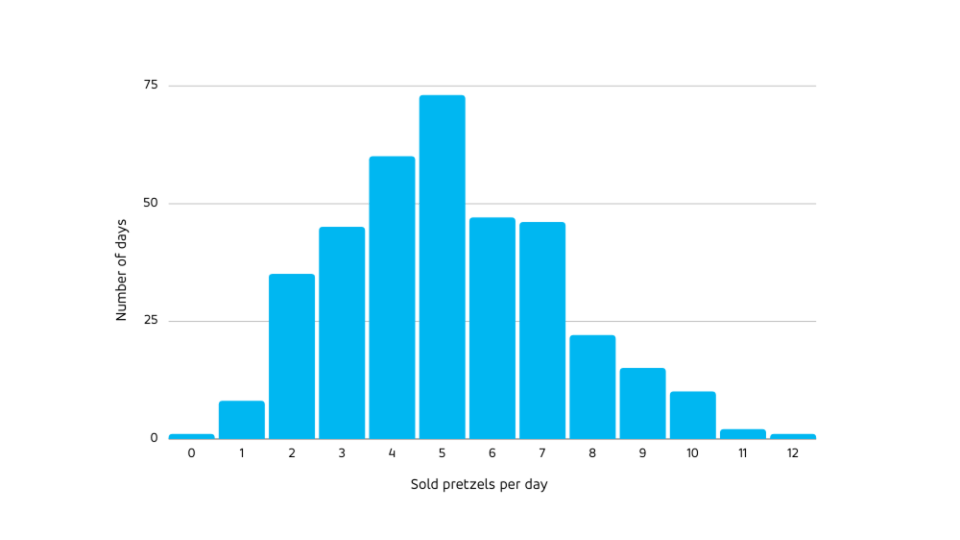

It turns out that retailers don’t offer items of extremely low demand because they cannot predict the actual demand precisely enough to find a profitable sweet spot in the balance between waste and out-of-stock-situations. Generally, a retailer’s business consists in turning consumer demand into actual sales. To know what and how much to have on stock, they need to estimate future demand as well as possible, be it via traditional, human-intuition based or via modern statistics — or even machine-learning-fueled forecasting. Until a few years ago, forecasts in supply chain have been concerned with large quantities on coarse-grained scales, e.g. the total sales of dairy products in a region during a month. Typical numbers that one dealt with were of the order of at least few hundreds, up to many thousands. Today’s computational resources allow forecasting on much more granular level, predictions refer to individual items on a single day in a given location. On that level, the typical numbers that we deal with are not in the 100,000s, but sometimes as small as 5, 1, or 0.1. Can we just transfer the established tooling for forecast assessment from the ‘large-number-world’ into the ‘small-number-world’?

Technically, no problems arise: A computer program written for larger numbers can be run on small numbers. Functionally, however, we need to take care: When moving to the regime of small numbers, statistical idiosyncrasies, which we could safely ignore in the fast-selling regime, become relevant or even dominating. When moving toward slow sellers, we start to experience the limits of forecasting technology: Just like any technology, forecasting has fundamental insuperable bounds. Both the forecast’s precision, the spread of actual demand around the forecasted value, and the forecast accuracy, the absence of bias towards systematically large or small values, cannot consistently overcome certain values, governed by statistical laws. We focus here on lower bound to forecast precision, on the unavoidable level of noise that a forecast of a countable quantity suffers from. This bound turns out to be scale-dependent: The relative uncertainty that we must live with in slow sellers is larger than in fast-sellers. This implies both that our forecast evaluation methodology must be scale-aware, and that you won’t be offered fresh sea cucumber in Rio de Janeiro.

.png%3Fh%3D480%26iar%3D0%26w%3D640&w=1920&q=75)